BLOG: “Ameca, do you like Taylor Swift?” Coming face-to-face with one of the world’s most advanced humanoid robots.

The chance for children to meet advanced humanoid robots like Ameca reveals the potential for artificial intelligence to enhance learning in schools, says Schools and Industry Engagement Lead at the National Robotarium, Michelle McLeod

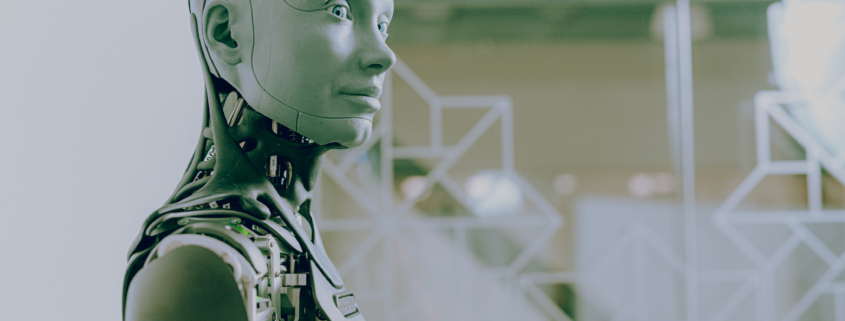

Last month, we welcomed students from Lasswade Primary and High Schools to the National Robotarium here at Heriot-Watt University to meet Ameca, one of the world’s most advanced humanoid robots.

As robots become more commonplace in classrooms and other child-focused environments, understanding how children form trusting relationships with these machines will be crucial. With this insight, we can design robots to more effectively collaborate with teachers and help to educate children.

We’ve done considerable research on human-robot interaction. One of our studies found that a robot’s ability to reliably perform its intended function is the most significant predictor of whether humans will trust it. In other words, if a robot consistently completes its tasks as expected, humans are more likely to have confidence in the machine.

A similar but separate study by scientists in Sweden, Germany, and Australia, shed some light on how children in particular perceive, and trust robots compared to humans. The research revealed that children tend to trust robots more than humans, believing that when the humans in the study made mistakes they were doing so on purpose, while the robots were not seen as making intentional errors.

So, why is trust between humans and robots so important? Their potential applications in education aside, it is increasingly likely that robots will become ubiquitous in the workplaces of the future so if we can get our young people comfortable living and working with them early, it will make that transition much easier.

This is why we invested in Ameca. We want to use it to engage with people of all ages to try and demystify robotics, to break down the barriers often associated with the apprehension of interacting with a machine that looks a lot like you.

Ameca’s makers, Engineered Arts, designed Ameca so that it mimics human behaviour as realistically as possible, maintaining eye contact and using familiar facial expressions and hand gestures, which are part of how humans interact with each other.

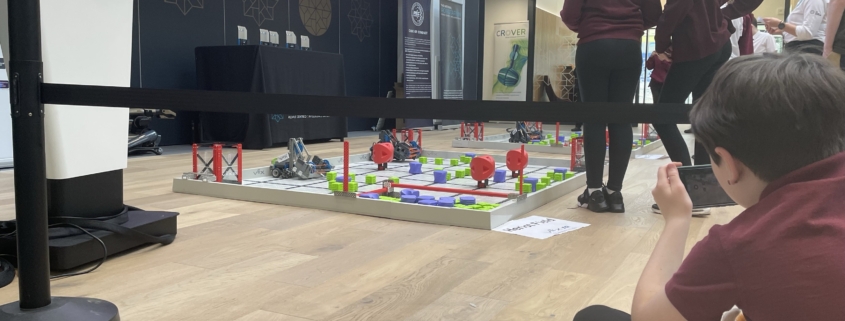

The young people who visited today were clearly awestruck by Ameca. Their eyes lit up when they walked through the door and saw it for the first time, some grinning from ear to ear, one little girl’s mouth dropped open, another mouthed a silent ‘wow’. They were initially unsure how to interact with Ameca but after a little prompting the questions started to flow.

“Would you like to be human?”, “Can you feel emotions?”, “What is 1,000 plus 1,000?”, and even, “Ameca, do you like Taylor Swift?”. (Turns out it does, or at least “can appreciate the emotional depth of her music”.)

The children then drew pictures for Ameca to identify. Most were of simple things like apples, or a spaceship, which it was easily able to recognise. Impressively, it was also able to identify that one child had drawn more irregular than regular pentagons on their page. Ameca’s blatant cheating at ‘Rock, Paper, Scissors’, however, making its choice after the child it was playing had revealed his, wasn’t so impressive.

By the end of the visit, the children were posing for selfies with Ameca, and a bond had clearly been formed. One little boy even returned to the room after a break, ran up to Ameca with his arms outstretched and shouted, “Ameca, it’s me, I’m back!”.

Ameca has limitations. It hasn’t been created to walk, for example, and does lose focus if too many people speak at once, so it won’t necessarily be the robot we find moving amongst us in the years to come but there is a higher purpose.

Research with school-aged children shows puppets , like a favourite doll or teddy bear, can encourage learning and improve communication and behaviour. Talking to a puppet, as opposed to a person, makes the conversation feel less personal and more pretend. It is a play-based technique sometimes used in therapy to help the child feel less self-conscious and open up.

We believe it’s the same with robots. In terms of interacting with artificial intelligence, for example, Ameca allows children to explore systems in a natural conversational manner, rather than battering questions into something like ChatGPT.

I think the questions the children were asking today showed their curiosity and interest in robotics and AI. That they so quickly adapted to Ameca was interesting, they were talking to it as if it was something more than a robot, as if it had a human personality. That’s a good sign.

Originally published in TES magazine on 24 July 2024.

Ben Glasgow

Ben Glasgow